Links

Industrial

Workers of the World

IWW Australia

IWW UK

Starbucks Union

Shattuck Union

IWW News

IWW Culture/Articles

Zinn

on IWW

The following excerpts were taken from "The Socialist Challenge," Chapter 13 of A People's History of the United States, by Howard Zinn

One morning in June 1905, there met in a hall in Chicago a convention of two hundred socialists, anarchists, and radical trade unionists from all over the United States. They were forming the I.W.W. -- the Industrial Workers of the World. Big Bill Haywood, a leader of the Western Federation of Miners, recalled in his autobiography that he picked up a piece of board that lay on the platform and used it for a gavel to open the convention:

Fellow workers. ... This is the Continental Congress of the working-class. We are here to confederate the workers of this country into a working-class movement that shall have for its purpose the emancipation of the working-class from the slave bondage of capitalism. ... The aims and objects of this organization shall be to put the working-class in possession of the economic power, the means of life, in control of the machinery of production and distribution, without regard to the capitalist masters.

On the speakers' platform with Haywood were Eugene Debs, leader of the

Socialist party, and Mother Mary Jones, a seventy-five-year-old white-haired

woman who was an organizer for the United Mine Workers of America. The

convention drew up a constitution, whose preamble said:

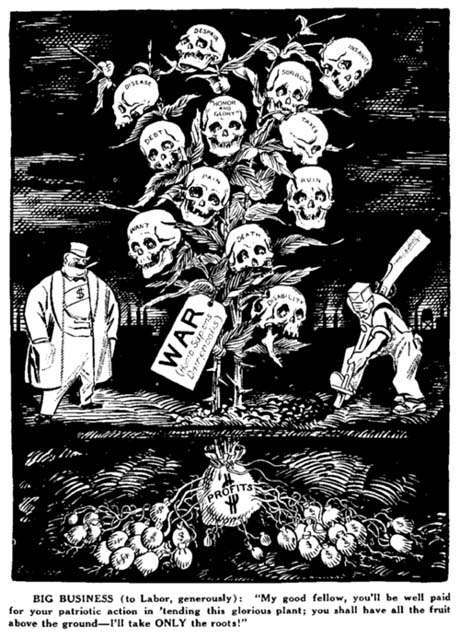

The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life.

Between these two classes a struggle must go on until all the toilers come together on the political as well as on the industrial field, and take and hold that which they produce by their labor, through an economic organization of the working class without affiliation with any political party . . . .

One of the IWW pamphlets explained why it broke with the AFL idea of craft unions:

The directory of unions of Chicago shows in 1903 a total of 56 different unions in the packing houses, divided up still more in 14 different national trades unions of the American Federation of Labor.

What a horrible example of an army divided against itself in the face of a strong combination of employers . . . .

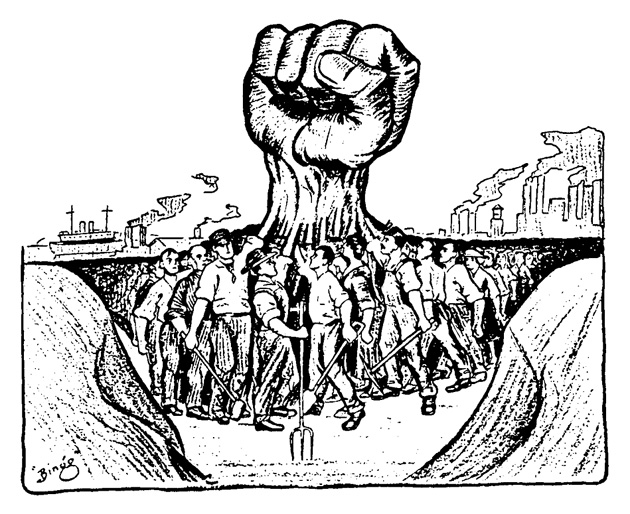

The IWW (or "Wobblies," as they came to be called, for reasons not really clear) aimed at organizing all workers in any industry into "One Big Union," undivided by sex, race, or skills. They argued against making contracts with the employer, because this had so often prevented workers from striking on their own, or in sympathy with other strikers, and thus turned union people into strikebreakers. Negotiations by leaders for contracts replaced continuous struggle by the rank and file, the Wobblies believed. They spoke of "direct action":

Direct action means industrial action directly by, for, and of the workers themselves, without the treacherous aid of labor misleaders or scheming politicians. A strike that is initiated, controlled, and settled by the workers directly affected is direct action. ... Direct action is industrial democracy.

One IWW pamphlet said: "Shall I tell you what direct action means?

The worker on the job shall tell the boss when and where he shall work,

how long and for what wages and under what conditions."

![]()

The idea of anarcho-syndicalism was developing strongly in Spain and Italy and France at this time -- that the workers would take power, not by seizing the state machinery in an armed rebellion, but by bringing the economic system to a halt in a general strike, then taking it over to use for the good of all. IWW organizer Joseph Ettor said:

If the workers of the world want to win, all they have to do is recognize their own solidarity. They have nothing to do but fold their arms and the world will stop. The workers are more powerful with their hands in their pockets than all the property of the capitalists . . .

In San Diego, Jack White, a Wobbly arrested in a free-speech fight in 1912, sentenced to six months in the county jail on a bread and water diet, was asked if he had anything to say to the court. A stenographer recorded what he said:

The prosecuting attorney, in his pleas to the jury, accused me of saying on a public platform at a public meeting, “To hell with the courts, we know what justice is.” He told a great truth when he lied, for if he had searched the innermost recesses of my mind he could have found that thought, never expressed by me before, but which I express now, “To hell with your courts, I know what justice is,” for I have sat in your court room day after day and have seen you, Judge Sloane, and others of your kind, send them to prison because they dared to infringe upon the sacred rights of property. You have become blind and deaf to the rights of man to pursue life an happiness, and you have crushed those rights so that the sacred right of property shall be preserved. Then you tell me to respect the law. I do not. I did violate the law, as I will violate every one of your laws an still come before you and say “To hell with the courts,” . . .

The prosecutor lied, but I will accept his lie as a truth and say again so that you, Judge Sloane, may not be mistaken as to my attitude, “To hell with your courts, I know what justice is.”

It

was an immensely powerful idea. In the ten exciting years after its birth,

the IWW became a threat to the capitalist class, exactly when capitalist

growth was enormous and profits huge. The IWW never had more than five

to ten thousand enrolled members at any one time; people came and went,

and perhaps a hundred thousand were members at one time or another. But

their energy, their persistence, their inspiration to others, their ability

to mobilize thousands at one place, one time, made them an influence on

the country far beyond their numbers. They traveled everywhere (many were

unemployed or migrant workers); they organized, wrote, spoke, sang, spread

their message and their spirit.

They were attacked with all the weapons the system could put together:

the newspapers, the courts, the police, the army, mob violence. Local

authorities passed laws to stop them from speaking; the IWW defied these

laws. In Missoula, Montana, a lumber and mining area, hundreds of Wobblies

arrived by boxcar after some had been prevented from speaking. They were

arrested one after another until they clogged the jails and the courts,

and finally forced the town to repeal its anti-speech ordinance.

In Spokane, Washington, in 1909, an ordinance was passed to stop street

meetings, and an IWW organizer who insisted on speaking was arrested.

Thousands of Wobblies marched into the center of town to speak. One by

one they spoke and were arrested, until six hundred were in jail. Jail

conditions were brutal, and several men died in their cells, but the IWW

won the right to speak.

In Fresno, California, in 1911, there was another free speech fight. The San Francisco Call commented:

It is one of those strange situations which crop up suddenly and are hard to understand. Some thousands of men, whose business it is to work with their hands, tramping and stealing rides, suffering hardships and facing dangers -- to get into jail . . . .

In jail they sang, they shouted, they made speeches through the bars to

groups that gathered outside the prison. As Joyce Kornbluh reports in

her remarkable collection of IWW documents, Rebel Voices:

They took turns lecturing about the class struggle and leading the singing of Wobbly songs. When they refused to stop, the jailor sent for fire department trucks and ordered the fire hoses turned full force on the prisoners. The men used their mattresses as shields, and quiet was only restored when the icy water reached knee-high in the cells. When city officials heard that thousands more were planning to come into town, they lifted the ban on street speaking and released the prisoners in small groups.

That same year in Aberdeen, Washington, once again laws against free speech,

arrests, prison, and, unexpectedly, victory. One of the men arrested,

"Stumpy" Payne, a carpenter, farm hand, editor of an IWW newspaper,

wrote about the experience:

Here they were, eighteen men in the vigor of life, most of whom came long distances through snow and hostile towns by beating their way, penniless and hungry, into a place where a jail sentence was the gentlest treatment that could be expected, and where many had already been driven into the swamps and beaten nearly to death. ... Yet here they were, laughing with boyish glee at tragic things that to them were jokes . . . .

But what was the motive behind the actions of these men? ... Why were

they here? Is the call of Brotherhood in the human race greater than any

fear or discomfort, despite the efforts of the masters of life for six

thousand years to root out that call of Brotherhood from our minds?

There were also beatings, tarrings and featherings, defeats. One IWW member, John Stone, tells of being released from the jail at San Diego at midnight with another IWW man and forced into an automobile:

We were taken out of the city, about twenty miles, where the machine stopped. ... a man in the rear struck me with a blackjack several times on the head and shoulders; the other man then struck me on the mouth with his fist. The men in the rear then sprang around and kicked me in the stomach. I then started to run away; and heard a bullet go past me. I stopped. ... In the morning I examined Joe Marko's condition and found that the back of his head had been split open.

In 1916, in Everett, Washington, a boatload of Wobblies was fired on by

two hundred armed vigilantes gathered by the sheriff, and five Wobblies

were shot to death, thirty-one wounded. Two of the vigilantes were killed,

nineteen wounded. The following year -- the year the United States entered

World War I -- vigilantes in Montana seized IWW organizer Frank Little,

tortured him, and hanged him, leaving his body dangling from a railroad

trestle.